Reflecting Historical Periods in Stage Costume

Ballet Royal de la Nuit

In 1969, Ballet for All (the Royal Ballet lecture-demonstration group) mounted a programme tracing dance from the French court of Louis XIV (1638-1715) to the birth of the Romantic ballet in the early 19th century. Designer David Walker was extremely knowledgeable about historic costume but also understood about translating it for contemporary audiences. So while his designs drew heavily on contemporary sources, what appeared on stage was far from dry historical reconstruction.

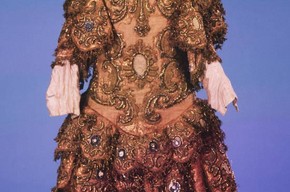

This costume is a 1970s recreation of an 18th-century design for a famous French ballet de cour. It recreates the outline and decoration of the original design and its impression of sumptuous richness while using materials of the 1960s - from the rich chestnut velvet to the furniture motifs and rosettes which are part of the opulent surface encrustations. The beautiful cut and fit and confident square neckline help suggest the elegance and authority of 18th century French aristocracy.

The costume is exceptionally heavy, which helped the dancers recreate the feel of 17th-century Court dances, which were stately and elegant, moving in a dignified manner across and into the ground, without the virtuoso jumps and spins of today's performers. However, like many theatrical period costumes the unseen area under the corselet has been replaced with heavy cotton, to make the costume lighter and more comfortable for the wearer.

Costume for PrЈІvost worn by Adeline GenЈІe in La Danse, designed by Wilhem, New York, 1912. Museum no. S.1460-1982

La Danse

This costume is from La Danse, a ballet tracing dance styles from 1710 to 1845. Adeline GenЈІe appeared as various star dancers from each period, ending with Marie Taglioni. Painstaking research was carried out to ensure that the costumes and music were as authentic as possible.

For her recreation of the great prima ballerina Françoise Prevost (1680-1741) no suitable image could be found. The designer Wilhelm based this costume on a print of Marie de Subligny, a dancer from the 1680s. The dress was immaculately copied, including the scroll work and jewelled stomacher, and shows Wilhelm's skill in transferring a black and white print into a three-dimensional costume. The costume was made by Miss Hastings, using only the highest quality fabrics and trimmings, which doubtless Wilhelm helped to choose. Only the construction of the bodice shows that it was made in the late Edwardian period.

The finished dress is elaborate and heavy, the bodice boned and the sleeves heavily flounced. The weight and detail of the finished dress suggest that GenЈІe was making a serious attempt to recreate the dance style of that period. In the late 17th and 18th centuries, costume restricted the movement of female dancers; boning meant that there was little flexibility in the torso although the arms moved slowly and gracefully; the long skirt meant that intricate footwork and spectacular jumps were impossible. Everything was judged on elegance and grace.

Miss Hastings' invoice describes the costume as: 'Louis XIV. For Miss GenЈІe consisting of:- Green and gold silk Brocade, Bodice and Train lined with shot green silk, trimmed with gold Lace, Jewels of Sapphires, Emralds (sic), Pearls, Gold Tassels, Blue Ninon Scarf printed in gold design. Headdress of Pearls with Feather Mount, Lace Sleeves, Necklace. Sundries, Skirt and Bodice embroidered and jewelled. £35.10.0' (about £2,400 today, in 1910 £35 would have paid a craftsman builder for 107 days' work). Costumes for the whole production cost just over £300 (ca. £20,400 today).

Love for Love

Costumes for Restoration plays (i.e. the late 17th century) are usually heavily pleated and flounced but this coat is slim line, emphasised by the vertical stripes and the back pleats are few and unstiffened (Der Rosenkavalier).

This is in keeping with the uncluttered, minimal look of the 1960s when the costume was made. The only opulent touch is in the richly embroidered cuffs.

When the production was revived in 1985, the costumes had to be cut more generously, as the audience was now used to fashion's fuller, romantic line. To have replicated the slimmer line of the original production, would have made people wonder if the theatre was skimping on fabric.

The subtle ochres and browns of the coat's striped fabric blended in perfectly with the muted tones of the sets. Several critics referred to the cat-like qualities of Olivier's performance and one wonders if that was suggested by this costume or whether Olivier's performance in rehearsal suggested a cat-like quality that de Nobili reflected in the costume.

Beneath the coat, in a typical de Nobili touch, is a waistcoat made of 18th century brocaded silk, far too fragile for the rigours of stage performance, but which is a wonderful contrast to the coat's dull surface. De Nobili was famous for her gleanings from the Paris flea markets, and wondrous antique fabrics and trimmings would be produced from her many bags and incorporated into the costumes, so that, as one critic put it, they 'arrived on stage with past lives.'

Costume for Elizabeth I in Benjamin BrittenЁЏs opera 'Gloriana', designed by Alix Stone, worn by Ava June, English National Opera, Coliseum, London, 1975. Museum no. S.15-2004

Gloriana

The costume retains all the obvious features of the Elizabethan period - the wide neck, rigid stomacher, elaborate sleeves and the huge farthingale skirt (the large neck ruff is missing). The making, however, is clearly 1970s, especially in the selection of materials. The main fabric is a woven lurex pattern on a background of then-fashionable apricot colour. The elaborate decorations are executed in other materials of the period - gold wired ribbons, gold netting, gold faceted beads and jewellery findings.

The costume structure is inbuilt and the stomacher, though quilted and with padded lining to give weight, has sacrificed historical accuracy for practicality, being much looser to allow the singer to breathe correctly.

Another costume for the same character in the Museum collection was made for the 1969 production, and the effects have been achieved very differently. The fabric is less bright in tone and part of the decoration is realised by 'drawing' on the fabric with gold resins, rather than constructing three-dimensional ornamentation.

The Sleeping Beauty

Costume for Princess Aurora in Act I of Marius PetipaЁЏs ballet 'The Sleeping Beauty', London, 1946. Museum no. S.55-1992

The classical ballet tutu, the plate-like skirt standing stiffly from the hips, would seem a unique costume, limited in scope. Yet the origin of this costume for Princess Aurora in Act I of The Sleeping Beauty is a historical source; Velasquez's 1656 painting Las Meninas, depicting the little Spanish Infanta.

Designer Oliver Messel realised that if the long falling skirt was removed from the Infanta's costume, the round farthingale does create a costume very like a classical tutu. Equally, the friends who accompany Aurora in Act I wear costumes very close to the figure in grey on the right of the painting.

Because of the demands of the choreography, Messel had to dress Aurora in a tutu in Act I, but as the scene takes place in the palace gardens on Aurora's 16th birthday, he wanted the idea of a day dress. By retaining the 'collar' around the upper edge and the long sleeves, he created a costume that gives the impression of a dress while remaining a classical tutu.

- ЩЯвЛЦЊЃКЗДгГдкЮшЬЈЗўзАРњЪЗЪБЦк 2013/12/8

- ЯТвЛЦЊЃКЩшМЦЮшЬЈЗўзА 2013/12/8